By Azmi Bishara *

Israeli politics is regulated by democratic principles based on Zionist

ideological tenets. The most important of these tenets are: The Jewishness of

the state, Aliya or the absorption of Diaspora Jews and Israeli citizenship

based on such values as military service, settlement and integration. It is

unmistakable that this structure is full of contradictions that strain

present-day Israeli political culture.

The relative modernity of this structure is at odds with the impossibility of

separating state and religion, because it is simply not possible to separate

between the Jewish religion and the Jewish nation, as well as between the right

of citizenship and affiliation to a religion because of the "(Jewish) right

of return." Historically, this type of Jewish democracy was built on the

vestiges of the Palestinian people and its social order, and is still held

captive by this paradox. Moreover, the paradox has been inflamed by Israel's

involvement in an occupation that forcibly abrogates a people's right to

self-determination on its native land.

These two paradoxes tie in with a third which is the main subject of this

article between the Zionism of the state on the one hand, and the proliferation

of democracy and equality to cover 20 percent of Arab citizens hailing from the

country's indigenous people and who stayed on after the Nakba (or 1948

catastrophe).

In terms of Western liberal democratic values, such a paradox is more harmful to

the democratic makeup of the state than the fact of occupying another people.

After all, most European democracies went through colonial periods that didn't

fundamentally affect the structures of their political systems.

While we beg to differ with this view, and even with such an analogy being made,

a democratic consensus has formed on the importance of equal citizenship as the

sine qua non of democracy, as well as the importance and sensitivity of the

issue of minority rights.

Issues such as these have no acceptable solutions in a situation where the state

is defined both as a Jewish state and as a state for Jews (not for its citizens)

at the same time.

That is why Israel has always tried hard to strike a balance between built-in

racial discrimination against Arab citizens on the one hand, and her need to

avoid appearing as an apartheid state within her international borders on the

other.

This balance was disturbed on several occasions, but was usually regained to the

advantage of Arab citizens who have benefited from an ever expanding margin of

rights. Arab citizens have on the whole been enjoying improving rights in the

Jewish state for a number of reasons, among which are the increasing power of

the Israeli ruling establishment, rising economic prosperity, and social

progress within the Arab community itself which has been increasingly vociferous

in its rejection of the gap separating its conditions from those of the Jewish

majority.

Nevertheless, and despite the enhancement of Arab rights compared to previously,

particularly when Arabs were subjected to direct military rule, the gap

separating the development of Arab and Jewish citizens has been widening. Nor

has the issue of racial discrimination been addressed.

Moreover, contradictions between the Arab citizens and state policies have been

increasing as a result of the amplification of national awareness amongst Arab

citizens for a variety of reasons we need not dwell upon here.

Israel did not engender an "Israeli nation" because it chose to

underscore the state's Jewish identity. At the same time, the wager on a crisis

of identity fragmenting the Arab citizens, marginalizing them and preventing

them from organizing themselves as a national group belonging to the Arab nation

and the Palestinian people proved misplaced.

Jewish democracy can tolerate Arab citizens as guests so long as they respect

the rules of hospitality. In other words, Israel can tolerate the presence of

those Israeli-Arabs who agree to remain on the margins of both Arab society and

Israeli society. She has no problems with co-opting those Arab citizens who

agree to transform themselves into half-Israeli, half-Arab hybrids

chameleon-like opportunists with no clearly defined cultural identity who try to

please both Israelis and Arabs at will; pathetically trying to win all worlds

after they have lost their own souls.

As a response to this phenomenon (which was gaining in strength and was on the

verge of pervading the mainstream), we have been trying to propose a democratic

ideological alternative that asserts a Palestinian Arab identity of different

hues of course, but not half-Arab.

Our proposal insists that full citizenship is a precondition for equality, and

there is a contradiction between full equality and the state's Zionist identity.

This contradiction is no reason for us to abandon our calls for equality; it

only stresses the fact that equality is at odds with Zionism. This is a problem

with Zionism, not with equality.

This liberal democratic thesis is seen in Israel as being so radical as to

almost violate the legal guidelines imposed on any ticket competing in

parliamentary elections. Since this message was adopted in the shape of a

political party running for parliamentary mandates, a new type of rivalry has

developed within the Arab community demanding more forceful assertion of its

Palestinian/Arab identity and total equality.

A campaign targeting Arab members of the Knesset (and Arabs generally), citing

their political positions vis-a-vis the Palestinian cause, has been escalating

ever since Benjamin Netanyahu came to office (in 1996). The objective has been

to de-legitimize Arab MPs on the pretext that their political loyalties clash

with their citizenship.

Incitement against Arab MPs within the Knesset reached a crescendo during the Intifada

by exploiting the contrived atmosphere of hostilities as well as the chauvinist

hysteria that overwhelmed and dominated public life in Israel.

During that period, the decision was taken to declare open war against Arab MPs.

I myself was shot in the shoulder by Israeli police in June 1999 while taking

part in a march to protest Israel's demolition of Arab homes in Lydda. The case,

however, was closed "for lack of evidence." Also, hundreds of Jewish

extremists attacked my house last October.

Again, no arrests were made, despite the presence of police at the time. In

fact, police assaults on Arab MPs became almost routine. There was no

"immunity" as such, save for the symbolic one preventing the state

from committing Arab MPs to trial.

For the first time in the history of the Knesset in which a member of Parliament

is stripped of his/her immunity for political statements he/she made, the

Israeli legislature recently stripped me of my parliamentary immunity. I was

indicted on two counts:

1. Accusations relating to statements I made on two occasions: in a protest

meeting held last June 5 at the village of Umm al-Fahm in which I expressed

sympathy with the Lebanese Hizbullah and appreciation for its role in rolling

back the Israeli occupation. The indictment states that these statements are

tantamount to terrorism. The second occasion was on the first anniversary of the

death of president Hafez Assad of Syria, in which I called on the Arab world to

support the Palestinian Intifada. The indictment says that this statement was a

call for using violence against the state.

2. Accusations relating to my interceding with the Syrian authorities in order

to enable some elderly Arab citizens to visit with their relatives living in

Palestinian refugee camps in Syria for the first time in 53 years. In a

humanitarian gesture that was much appreciated by Arabs in Israel, Syria agreed

to this request. Israel, meanwhile, didn't dare prosecute elderly people for the

"crime" of meeting with their relatives possibly for the last time. So

they prosecuted Azmi Bishara for "organizing visits to hostile countries

without the permission of the Israeli government."

Despite the fact that my colleagues and I have to deal with these indictments

seriously, and prepare a robust defense in order to prove my innocence, we

realize that the accusations leveled against me are political in nature with

political motives and political objectives.

The accusations are political in essence because they are based on Israel's

political viewpoint which considers legitimate resistance to be a form of

terrorism. The political motive is based on a right-wing Zionist conviction that

democratic pluralism must be limited by allegiance to the Israeli/Zionist state.

Israel's political objective is to undermine the Democratic National Assembly (Balad)

by prosecuting its leadership, and by terrorizing Arab citizens into withholding

their support.

That is why our trial must be met with a widespread public reaction that

expresses support for Balad's objectives and shows Israel that Arabs cannot be

cowed into submission. The trial must also be accompanied by a political debate

about the distinction between legitimate resistance and terrorism.

We consider occupation to be a form of political violence directed against

innocent people. It is, in other words, a form of terrorism. Similarly, we

consider resistance to occupation within certain political and moral constraints

to be part of the fight against terrorism.

Israel will try to project my case to liberal opinion in the West as "a

democracy defending its existence." Besides my avowed position about how

democratic the state of Israel really is, I maintain that the claim is invalid

in my case in fact it is turned on its head.

It is we who represent democracy fighting for survival against an assault

launched by forces that are by definition anti-democratic. The majority which

voted in the Knesset to lift my parliamentary immunity was constituted of

movements and forces that are neither liberal nor democratic. Among those

movements were extreme right-wing parties and ultra-orthodox parties.

Democracies usually fight for their survival against such parties. The upcoming

trial, therefore, presents a rare opportunity to discuss how democratic a

country Israel really is.

In this saga, the so-called Zionist left has shown not only how impotent it is,

but also its moral bankruptcy. To prove that their party is no less patriotic

than the Likud, many Labor MPs voted for lifting immunity. Those lawmakers who

voted against (such as MP Yossi Sarid), meanwhile, justified their position by

saying that they voted for freedom of expression after launching a bitter

campaign of lies and slander against me worse than any of the right ever

attempted.

The Israeli left distorts our positions, incites public opinion against us, then

tries to prove its moral superiority by defending the "freedom of

expression in Israeli society." The battle is not over freedom of

expression, nor is the Israeli left a believer in the principles of Voltaire. My

statements would not have been noticed nor would we have been indicted if we

didn't represent a genuine political force, and had there not been a decision to

undermine Arab political representation.

The battle, therefore, is over Arab representation. It is about our right as

Arabs to organize, about our right to interact with our people suffering under

Israeli occupation, and, finally, about the compatibility of Zionism with

democracy and equality.

* Member of Knesset and the leader of the National Democratic

Coalition. Bishara was stripped of his parliamentary immunity by the Israeli

legislature two weeks ago.

| PalestineRemembered | About Us | Oral History | العربية | |

| Pictures | Zionist FAQs | Haavara | Maps | |

| Search |

| Camps |

| Districts |

| Acre |

| Baysan |

| Beersheba |

| Bethlehem |

| Gaza |

| Haifa |

| Hebron |

| Jaffa |

| Jericho |

| Jerusalem |

| Jinin |

| Nablus |

| Nazareth |

| Ramallah |

| al-Ramla |

| Safad |

| Tiberias |

| Tulkarm |

| Donate |

| Contact |

| Profile |

| Videos |

THE ISRAELI DEMOCRACY! |

What is new?

-

Facts About Oct. 7th Gaza Raid

-

Remined Us Please:: Who Did Rape Who? Palestinians Raped Israelis? Or, was the other way around?

-

When Prof. Edward Said was invited to debate Bibi Netanyahu in the 1980s, watch what happened!

-

Ezra Klein of the NY Times on the "Jewish Race".

-

Abusing Blood Libel!

-

Did Israeli Soldiers Activate The Hanniba Direective On Oct. 7th? You Be The Judge

-

Zionist FAQ: Isn't it true that Palestinians don't want peace? Palestinians never accepted the two-state solution

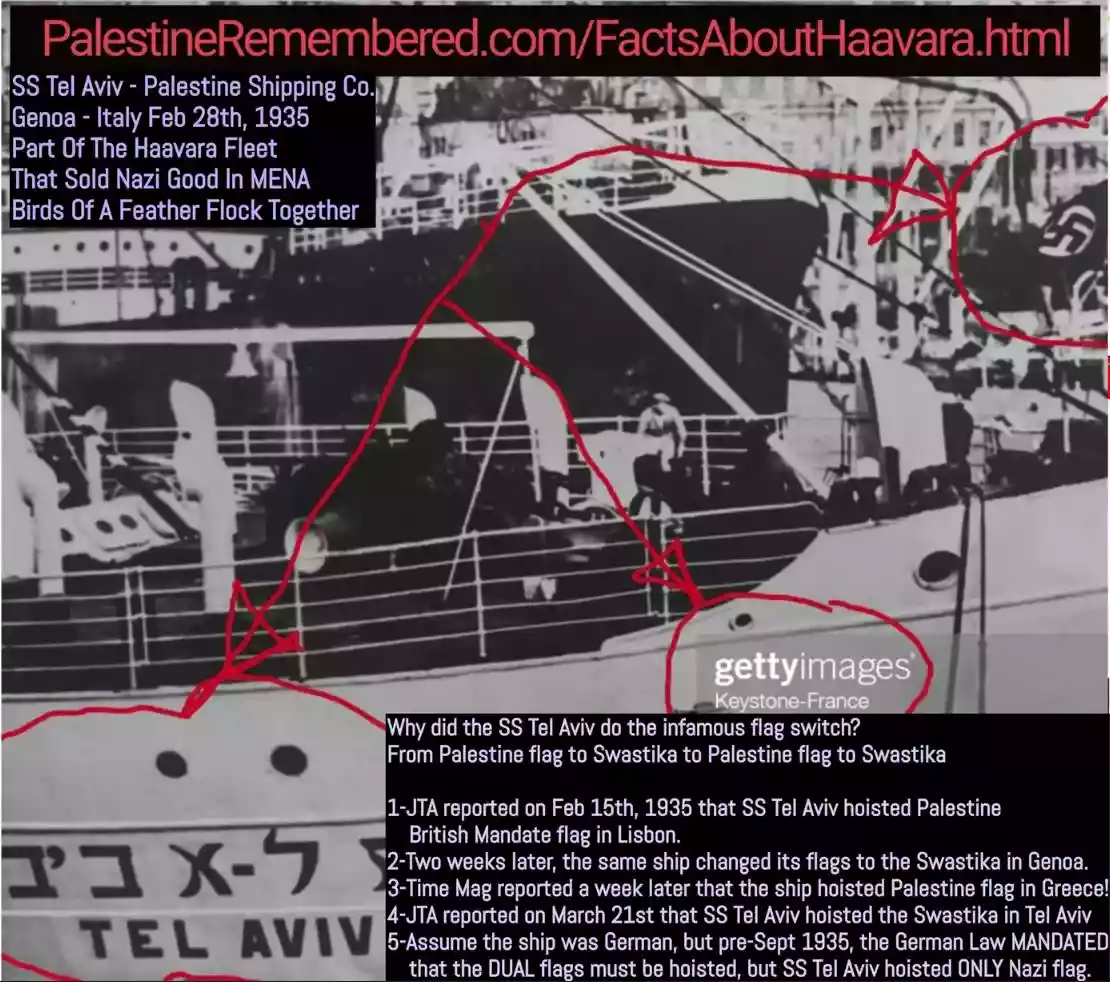

- Facts about Haavara (Transfer) Agreement between Ben-Gurion & Hitler

-

Haavara FAQs: Why Did Zionist Jews Hoist Nazis' Flags on Their Ships in the 1930s?

- Haavara FAQs: When Chaim Weizmann met FDR in mid-1943, why was he silent about rescuing European Jewry?

-

Dear ChatGPT: How did Palestinians resist Napoleon's invasion of their country in 1799?

-

Dear ChatGPT: Gaza had a vibrant Jewish community in the mid-17th century. What happened to them?

-

Dear ChatGPT: Why did the Jewish Agency suppress news of the Holocaust during WWII?

-

Video Playlist: Jews share their DNA tests to end the conflict for good.

-

A Tale of Two Conflicts: Examining the Definition of Genocide

-

Prof. Abraham Polak And The Suppressed History of the Khazars and European Jewry

-

How Ronald Reagan would have framed the genocide in Gaza if he were still alive?

-

Haavara FAQs: Let us do the math: how many German Jews did The Haavara Agreement save?

-

Zionist FAQs: The Hebron Massacre of 1929, "clearly proves" that Palestinians are antisemitic, how could you deny it?

-

Zionist FAQs: Why Anti-Zionist Is Not Antisemitism?

-

Zionist FAQs: Isn't it true that the KGB created Palestinian Nationalism in the early 1960s?

- Zionist FAQs: Muslims are killing Muslims all the time; why are Israeli Jews being singled out in the media?

- Zionist FAQs: How is Israel an apartheid state when 20% of its citizens are Arabs who enjoy full rights?

-

Haavara FAQs: Why Did Dorothy Thompson Flip From A Zionist Advocate to A Silenced Dissenter?

-

Haavara FAQs: Analysis of Herzl's Uganda Scheme and how it could have saved millions of Jews.

-

Haavara FAQs: Why did Hayim Greenberg describe American Jewry as "morally bankrupt" in early 1943?

-

Haavara FAQs: What if the Evian Conference was a resounding success? What would have been the impact of saving European Jewry on Zionism?

- Haavara FAQs: What if the six million were saved, how that would have impacted the Zionist project?

-

Haavara FAQs: How did Zionist leaders react when Europe's Jews lingered in the DP camps after WWII ended?

-

Why does the American Jewish community repeat lies that David Ben-Gurion had debunked before he died?

-

Who has the power to rename the Tatar/Khazar Gene Marker to Jewish IV?

-

Zionist FAQs: Why won't Egypt, Syria, and Jordan take their people back? Jews are indigenous to Palestine, and Arabs immigrated after Jews developed the country. Arabs should leave.

-

Haavara FAQs: Did Hitler and the Nazis conflate between Judaism and Zionist? If that wasn't case, then why?

-

Haavara FAQs: Winston Churchill and antisemitism, a collection of articles written Churchill.

-

Haavara FAQs: Broken by country, how many Jews survived vs. killed during the Holocaust?

-

Haavara FAQs: Why did European Jews vote with their feet and to immigrated to the Americas, not Palestine, after WWII?

-

Watch this American Jewish Girl describing Israeli Jews' cognitive dissonance like no other in under two minutes

-

Haavara FAQs: When the Nazis went out of their way to hide the Holocaust, Israeli Jews did the exact opposite by broadcasting their genocide of Gazans. But why?

-

Haavara FAQs: How Zionist Jews went out of their to show their appreciation to Nazism and Fascism?

- Haavara FAQs: Why Zionist leaders were against bombing the death camps & the Railroads leading to them?

-

Haavara FAQs: Hitler's message to the British and American people: If Jews are such noble citizens and you care about them, how come you're not letting them in? I will gladly ship them to you at my expense, even on luxury liners!

-

A shortlist of Zionist and Israeli false flag operations in the name Jews.

-

The Most Moral Army

- The Land of Kapos (Israel): Where the brave are boycotted and Kapos walk free.

- Why did early Zionists often named their communal enterprises "colonial"?

- Zionist Relations with Nazi Germany by Faris Glubb

-

Two NY Times advertisements by Zionists in the early 1943 that exposes Zionists' treason at the height of the calamity

- Facts Not Lies about the Palestinian-Israeli Conflict.

- Site's pictures have been categorized

- Campgain Against Lice

- A Survey of Palestine, the official source about Palestine before Nakba produced by the British Mandate; over 1200 pages.

- Satellite View & Google Earth: Over 6,000 placemarks identifying all destroyed towns, W. Bank & Gaza Strip Towns, & refugee camps.

- PalestineRemembered.com and its Nakba Oral History Project were featured on al-Jazeera Satellite TV.

- Nakba Oral History Video Podcast:

Over 700 Oral History interviews (including 3,500+ hours of recording) can be viewed online.

Over 700 Oral History interviews (including 3,500+ hours of recording) can be viewed online. - Palestine Village Statistics Project

- Gaza Jail Break

- النسخة العربية للموقع الان متوفرة

- Videos: Documenting the destroyed villages in video: Tracing all that remains since Nakba.

- Videos: Responding to Zionist Propaganda

- Interview: The ethnic cleansing of Palestine: George Galloway interviews Israeli Historian Ilan Pappe.

- For Palestinians, memory matters. It provides a blueprint for their future By George Bisharat.

- Zionist FAQ now available in Hebrew שאלות שציונים שואלים, עכשיו בעברית

- Video: The Stephen Walt and John Mearsheimer report on the influence of the Israel Lobby on U.S. Foreign Policy

- The Palestinian-Israeli conflict for beginners

Home |

Mission Statement |

Zionist FAQ |

Maps |

Refugees 101

Zionism 101| Zionist Quotes | R.O.R. 101 | Pictures

Ethnic Cleansing 101 | Search | Chronology | Conflict 101

Your Profile | Looting 101 | Contact | Oral History | DONATE

Privacy Policy

© 1999-2025 PalestineRemembered.com all rights reserved. All pictures & Oral History Podcast are copyright of their respective owners.

Zionism 101| Zionist Quotes | R.O.R. 101 | Pictures

Ethnic Cleansing 101 | Search | Chronology | Conflict 101

Your Profile | Looting 101 | Contact | Oral History | DONATE

Privacy Policy

© 1999-2025 PalestineRemembered.com all rights reserved. All pictures & Oral History Podcast are copyright of their respective owners.

Post Your Comment

*It should be NOTED that your email address won't be shared, and all communications between members will be routed via the website's mail server.