Introduction

Palestine was one of the main destinations for Jews fleeing Nazi Germany in the 1930s. Though compared to the magnitude of the refugee crisis, the number of immigrants and refugees from Nazi-ruled countries who settled there between 1933 and 1940 was small, nonetheless, with about 60,000 immigrants, it was second only to the United States as a country of refuge. (1) The number of Jewish immigrants and refugees from Nazi Germany who found asylum in Palestine was principally determined by the policy and attitudes of Britain -- the Mandatory power that ruled the country -- and to a much lesser extent by those of the Zionist Organisation, which was entrusted with partial responsibility for Jewish immigration into the country. The developments in Germany were not the sole or even the main factor in shaping these policies and attitudes, which were moulded first and foremost by Britain's overall considerations and by the unique status of the Zionist Organisation and the complexity of its obligations.

To understand the role of Palestine as a destination for Jews from the Third Reich, we must first introduce the main actors in the Palestinian arena and the rules regulating immigration into the country. The article will then portray and analyse the reactions of Britain and of the Zionist Organisation to the deteriorating situation of the Jews in Germany after 1933 and in Austria after 1938 until the beginning of the Second World War. It should be borne in mind that Palestine did not constitute a typical destination for immigrants, being small, poor, lacking in natural resources, most of whose area could not be cultivated using the available methods of the time, and with a majority of its population, the Arabs, opposing Jewish immigration. On the other hand, the Yishuv (the Jewish community in Palestine) had an inherent interest in immigration. The Yishuv was an immigrant society, the majority of whose members were first generation immigrants themselves, many with relatives abroad whom they were eager to bring to Palestine. In addition, Zionist ideology had conditioned the Yishuv to adopt a favourable attitude towards further Jewish immigration into Palestine, and made it an integral component of the Zionist ethos. Ideological commitment and personal obligation towards immigration prevailed even when -- at least in the short run -- the flow of newcomers harmed the (Jewish) 'natives' and countered their immediate interests. Unlike other countries, where, in times of economic depression, trade unions were among the leading 'restrictionist' forces, the General Federation of Jewish Labour (Histadrut) favoured large-scale Jewish immigration even when unemployment was high.

A brief clarification regarding the use of the terms 'immigrant' and 'refugee' also needs to be made. Rules in the British Mandate regulating immigration into Palestine assumed all incoming Jews (except tourists) to be permanent 'immigrants'. A few months before the Second World War, a special quota for 'refugees' was established for the purpose of allowing persecuted Jews to enter Palestine as a final destination. From the Zionist point of view, immigration to Palestine was the ultimate realisation of Zionist ideology and every Jew was welcome to settle in Palestine no matter how he or she arrived there, with whatever motivation and for whatever reason or purpose. Once a Jew had entered Palestine, he or she was no longer considered a refugee but rather an equal member of the existing community. A more suitable term might be 'repatriate', even if the label 'refugee' conforms to international law and universal tradition. As for German Jews who moved to Palestine after Hitler's rise to power, there is no way of knowing whether the immigrant was a long-time Zionist who had intended to immigrate to Palestine at some point anyway, and the new situation only hastened his departure; or whether he had been forced out of Germany, but once he had to emigrate, Palestine was his first choice; or whether Palestine was just the most available destination and a staging post for the first opportunity to move on to another destination. Therefore, unless the reference is to a legal definition or to a case in which either the term 'immigrant' or 'refugee' is the unequivocally suitable definition, those terms are used interchangeably. Finally, the main focus of the chapter is Zionist activity in relation to the immigration of Jews from Nazi Germany to Palestine, and it is in this field that the chapter puts forward new empirical elements and interpretations. The policies, attitudes and motivations of the British and the German authorities are brought out as essential components of presenting the issue and analysing it, as well as a background to the Zionist policy.

Immigration Policy and Regulation in the Palestine Mandate

In 1922, the League of Nations entrusted Britain with 'full powers of legislation and of administration' over Palestine, and made her 'responsible for placing the country under such political, administrative and economic conditions as will secure the establishment of the Jewish national home'. At the same time, Britain proclaimed that 'for the fulfilment of this policy it is necessary that the Jewish community in Palestine should be able to increase its numbers by immigration', but went on to say that 'it is essential to ensure that the immigrants should not be a burden upon the people of Palestine as a whole, and that they should not deprive any section of the present population of their employment'. (2) From the outset, Britain detached its Palestinian policy from the situation of the Jews in Europe, and insisted that immigration to Palestine was not to be expected to supply the solution for deprived or persecuted Jews. (3)

Until 1937, immigration to Palestine was officially regulated in accordance with the economic absorptive capacity of the country. However, in the 1930s, immigration was in fact primarily governed by political rather than economic considerations. (4) The main concern of the British authorities was to ensure law and order in the country, and they were attuned to the complaints of the Arabs that Jewish immigration harmed them economically and threatened their status as the majority in the country. In 1934, when Jewish immigration grew rapidly and substantially, Britain came to the conclusion not to allow the Jews to become the majority group in the country. (5) In the second half of the decade, following the Arab Revolt that broke out in 1936 and continued until late 1939, Britain acted to maintain the existing demographic composition of Palestine (about one-third Jews and two-thirds Arabs). In July 1937, it formally abandoned the principle of economic absorptive capacity as the yardstick for Jewish immigration, replacing it with the 'political high level' principle aimed at preventing the growth of the Jewish population beyond the one-third limit. This 'political high level' principle fixed a ceiling on Jewish immigration of all types, ages and sexes, determined by political and demographic considerations, regardless of the country's economic ability to absorb immigrants. In 1937, it was set at 12,000 immigrants per year; (6) in the May 1939 White Paper, the number was raised to 15,000, (7) reflecting the rapid natural growth of the Arab population in Palestine.

Immigration regulations in the Mandate divided immigrants into four groups: Persons of independent means (Category A, 'Capitalists'); Students and persons of religious occupations whose maintenance is assured (Category B); Persons who have a definite prospect of employment (Category C, 'Labour'); Dependants of permanent residents of Palestine or of immigrants in other categories (Category D). Only category C immigrants were subject to the economic absorptive capacity principle, as the immigrants of categories A, B and D were not expected to join the labour market. Therefore, until 1937, there was no limit on the number of immigrants in these categories, and most importantly on that of persons of independent means. A special quota for 'refugees' was established only as late as May 1939. (8) Britain alone regulated the immigration of categories A, B and D, granting the Zionist Organisation partial authority over the issue of category C certificates in return for its undertaking to guarantee the maintenance of the immigrants during their first year in Palestine.

The Zionist Organisation and Its Role in Immigration to Palestine

The Zionist Organisation was founded in 1897 for the purpose of establishing an independent Jewish political entity in Palestine. It functioned as a Parliamentary Democracy, its constituency composed of all those who paid membership dues (The Zionist Shekel). Elections to the Zionist Congress (the Parliament or the legislator) were held every other year. A newly elected congress, convened only once, voted on an Executive formed by coalition agreements. The Zionist Organisation was a voluntary association lacking any attributes of a sovereign state and its leadership barely had the means to enforce its decisions. The Zionist Organisation's limited authority over some immigration matters constituted one of the few bases of power held by its leadership. The labour certificates were the most precious resource that the Zionist Organisation controlled and could dispense among its 'citizens'. In the 1930s, the certificates were distributed first and foremost on political grounds: the various Zionist parties would make promises regarding immigration prospects and then competed in providing this benefit to their members. Prospects of receiving a labour certificate were a weighty incentive for joining the Zionist Organisation, and calculation, even speculation, as to the probability of getting one had some bearing on the decision of which party to join. To sum up, the distribution of the certificates had some effect on determining the balance of power in Zionist institutions. Furthermore, since immigration was the main source of growth for the Yishuv, distribution of the certificates also played a role in shaping its political structure.

From its inception, the Zionist organisation was caught in an inextricable tension between the devastating and oppressive conditions in which masses of Jews lived in various countries, and the limited and gradual solution that Zionism was able to offer. After the First World War, the League of Nations recognised the Zionist Organisation as the representative of the Jewish people in all matters concerning Palestine, (9) and the Mandatory power granted it limited authority to regulate some immigration matters. (10) However, the latitude in decision making that the Zionist Organisation had in general, and in immigration matters in particular, was so limited that it is doubtful whether is it appropriate to speak of Zionist immigration 'policy' in the sense of exploring alternatives and then choosing a course of action. The Zionist Organisation had no influence over the volume of immigration, and it was Britain that determined the rules of the game and always had the final say. The small number of immigration certificates given to the Zionist Executive in the two years preceding the outbreak of the Second World War made the administration of Zionist immigration policy a matter of theory and left the Zionist Organisation with almost no room to manoeuvre, to apply discretion or to offer substantial solutions to the plight of the Jews of the Third Reich. In the 1930s, the Zionist Organisation encompassed a relatively small proportion of the Jewish people, and it neither considered itself, nor was it regarded by most Jews, as representing the interests of the entire Jewish people. Consequently, it was not held solely responsible for the fate of the Jewish people, nor was it expected to provide an overall solution to the refugee crisis.

The Reaction of Britain, the Mandatory Power, to the Refugee Crisis 1933-1939

From 1933 on, Britain granted Jews from Germany (and in 1938-9 from Austria as well) a preferential status in immigration into Palestine. On almost every schedule of type C certificates (published twice a year), the Mandate Government allotted a specific number of certificates to Germany, or directed the Zionist Executive to do so. It also allotted a certain percentage (5 to 10 per cent) of the labour schedule to male immigrants from Germany aged 36-45, while the maximum age for labour immigrants from other countries was 35. Another affirmative step in favour of German Jews was qualifying professionals from Germany who had only one year's experience to receive certificates as skilled experts, instead of the eight years demanded of candidates from other countries. Britain did not supplement this favouritism towards German Jews with an increase in the total number of certificates, but rather made a change in the apportioning of the cake. In other words, the generosity of Britain toward German Jews in immigration to Palestine resulted in diminished immigration opportunities for Jews from other countries. This was also the case when in May 1939 the MacDonald White Paper set up a special quota for refugees. First, Britain decided that in the following five years, 75,000 Jews would be allowed to enter Palestine, 'a rate which ... will bring the Jewish population up to approximately one third of the total population of the country', and then it announced that:

[T]hese immigrants [will] ... be admitted as follows: For each of the next five years a quota of 10,000 Jewish immigrants will be allowed ... In addition, as a contribution towards the solution of the Jewish refugee problem, 25,000 refugees will be admitted ... special consideration being given to refugee children and dependants. (11)

The May 1939 White Paper was formulated under the shadow of an imminent world war, with the purpose of placating the Arabs in Palestine and in neighbouring countries in order to ensure their support for Britain should war break out. It was clear to the British policy makers that the most important measure that could be taken to achieve this goal was to meet the Arab demands concerning immigration. (12) However, as stated in paragraph (14) of the White Paper, an abrupt stop to further Jewish immigration into Palestine:

would damage the whole of the financial and economic system of Palestine and thus affect adversely the interests of Arabs and Jews alike. Moreover, [it] would be unjust to the Jewish National Home. But, above all, His Majesty's Government are conscious of the present unhappy plight of large numbers of Jews who seek a refuge from certain European countries, and they believe that Palestine can and should make a further contribution to the solution of this pressing world problem.

The White Paper clearly reflects the fluctuation of the British between their various obligations and interests. Thus it also stated that 'after the period of five years no further Jewish immigration will be permitted unless the Arabs of Palestine are prepared to acquiesce in it', and went on to declare in paragraph 15 that 'His Majesty's Government are satisfied that, when the immigration over five years which is now contemplated has taken place, they will not be justified in facilitating, nor will they be under any obligation to facilitate, the further development of the Jewish National Home by immigration regardless of the wishes of the Arab population'. Shortly after that, following the outbreak of the Second World War, Britain prohibited people from Germany or from German- occupied territory from entering Palestine, and thus the effect of the refugee clause almost totally lapsed. (13)

The Zionist Reaction to the German Crisis

The German crisis of 1933 placed the Zionist Organisation in an unprecedented situation. For the first time in history, an entire Jewish community was confronted with aggressive anti-Semitism when hardly any immigration destinations were available. The crisis put Zionism to the test, and Zionist leaders were concerned lest their failure to provide meaningful solutions would prove their ideology to be obsolete and their cause irrelevant. The Zionist response to the German crisis evolved as a series of reactions to the unpredictable but constant changes in the German policy towards the Jews. (14) Zionist leaders were puzzled as periods of intensive persecution were followed by interludes of eased tension, when it seemed that the threat was over. As a rule, until November 1938, they widely conceived the situation of the Jews of Eastern Europe and particularly of Poland, as worse than that of their brethren in Germany. From the very beginning of the crisis the Zionist Executive aspired to turn the plight of Germany's Jews into a lever for increasing Jewish immigration into Palestine. One of its first reactions was an appeal to the British High Commissioner to grant special quotas of Labour certificates for German Jews. He agreed to do so but only by taking the special allotment for German Jews from the general pool of certificates. (15) This course of action posed moral dilemmas for the Zionist Organisation, since it was a matter of a zero-sum game, and organisational difficulties as well. Membership of the Zionist Organisation or affiliation with a Zionist movement, party or association was generally a prerequisite for receiving a category C (Labour) immigration certificate. German Jews constituted a relatively small fraction of the Jewish population in Europe and an even smaller proportion of the Zionist Organisation membership. Internal political calculations, feelings of obligation towards veteran members of the Organisation in East European countries and estimations of the relative danger and distress of the various Jewish communities, all provided apparently insoluble problems for the Zionist leadership when they had to distribute the labour certificates.

From the beginning, some Zionist leaders and functionaries anticipated that granting a significant portion of the certificates to German Jews would diminish the immigration prospects of Polish Jews, a situation which in its turn would cause desperation among Jewish youth and push them into the arms of Communism. (16) At the eighteenth Zionist Congress (August 1933), the first to convene after Hitler's rise to power, one of the experts on the resettlement of German Jews, himself of German descent, warned of focusing the entire Zionist and Jewish efforts on bringing German Jews to Palestine because it would hurt potential immigrants from other countries. 'Palestine does not exist only for German Jews. ... Its gates have to be open to Jews from other countries as well'. (17)

The number of members of Zionist pioneer organisations in Germany, which served as vehicles for immigration to Palestine of young men and women under the labour schedule, grew rapidly from about 500 in April 1933 to 2,800 in May and reached 14,000 by the end of that year. (18) An emissary of the Histadrut to Germany reported mass enrolment in the pioneer organisations since Hitler's rise to power, and warned that 'the quality of this material is doubtful. ... From the Zionist point of view it is very questionable material'. (19) The term 'Hitler-Zionist' was in common use as an expression to describe what was generally conceived to be the motivation of German Jews in joining the Zionist Organisation. Another measure that turned the plight of Germany's Jews into a lever for increasing Jewish immigration into Palestine was the establishment of numerous funds and institutions dedicated to aiding them to leave Germany and to be resettled in Palestine. (20) Monies raised by the special funds for the migration of German Jews to Palestine were earmarked, and could not be spent for any other purpose, not even for the absorption of Jews from other countries. The Zionists worried that if they did not make good use of the money, donors would divert their funds to the relocation of German Jews elsewhere.

As early as 1933, the urge to increase the number of wealthy immigrants from Germany under Category A (Persons of independent means, or 'Capitalists'), led to the signing of the so-called Ha'avara Agreements with German authorities, allowing Jews to take a larger proportion of their money and property out of Germany than the existing regulations allowed. The results of this scheme will be discussed below.

An Interlude: 1934-1935

In the summer of 1933, after the first wave of persecution against Jews in Germany had subsided, criticism over the changes in the geographical allocation of the certificates was publicly expressed. 'How come ... it is the German [Jews] who became privileged', argued a member of the Zionist Executive, known as an advocate of Polish Jews' rights in immigration. (21) In April 1935 the Histadrut resolutely demanded an increase in the number of certificates designated for members of the pioneer movements in Poland by reducing the allotment to Germany. (22) So numerous were the complaints about the favourable status given to Germany and the inequity towards other countries in the distribution of certificates that the Immigration Department of the Jewish Agency pleaded for a cessation of the protest letters or telegrams regarding the number of certificates allocated to each country. It went on to explain that its course of action had been taken because of the explicit dictate of the government to grant one-third of the certificates to immigrants from Germany. (23)

The Zionist Executive, which had actually initiated the affirmative action in favour of German Jews, eventually found itself trying to curtail the preference given them by the government. For example: in the spring of 1934, the government demanded that 50 per cent of the certificates be granted to Germany (including German refugees in neighbouring countries), while the Zionist Executive wanted to give them only 33 per cent and at most 40 per cent, claiming that at that time there were not that many qualified persons in Germany who had completed their term of training for agricultural work in Palestine, while thousands of trained young people were waiting their turn to immigrate in Austria, Czechoslovakia, Poland, and other countries. (24)

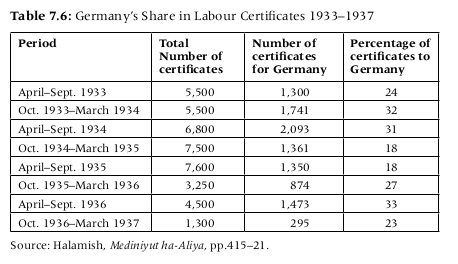

The conjuncture of an extended relatively calm period in Germany with the easing of the government requirement to grant Germany a substantial number of certificates, caused a decline in Germany's share in the labour schedules (see Table 7.6), and it was the turn of the German Jews to complain. In May 1935, the Association of Immigrants from Germany (Hit'ahdut Oley Germania) protested the Executive's allocation of certificates for immigrants from Germany, and presented absolute and relative numbers to show that Germany's share in the labour schedules had declined from 33 per cent in 1933 to 24 per cent in 1934 and to 17.7 per cent in 1935. (25)

The Nuremberg Laws, September 1935

The reaction of the Zionist Organisation to the Nuremberg Laws of September 1935 was shaped by two concurrent developments. One was deterioration of the situation of the Jews in Poland after the death of Polish President Pilsudsky in May, and the other was the drastic reduction in the number of labour certificates (the schedule for the autumn 1935 season was 3,250 compared to 8,000 in the spring of that year). In an attempt to utilise the renewed interest in the fate of German Jews following the adoption of the Nuremberg Laws in its struggle to prevent the drastic cut in labour immigration, the Zionist Executive asked the government for an advance of 2,000 certificates, half for trained young persons who had been living for a long time in training institutions in Germany and were ready for immediate immigration. The government granted the Executive only 1,000 certificates of which 750 were given to Germany. (26) As had previously been the case, the special allotment of certificates to Germany automatically reduced the quantity given to other countries.

The preference given to German Jews was not limited to the allocation of certificates but was evident in the absorption process as well, and complaints were voiced over inequality in the treatment of new immigrants from different countries of origin. (27) The absorption of German Jews was not financed solely by the special funds earmarked for them but also by the regular Zionist budget. For instance: the British Council for German Jewry allotted one hundred pounds for every German Jew who joined an agricultural settlement in Palestine; however this amount did not cover the full cost of absorption and the Jewish Agency had to supplement it with much higher sums, taken from other parts of the Zionist budget. (28)

The Anschluss, March 1938

The annexation of Austria to the Reich in mid March 1938 struck a severe blow to about 182,000 Jews living in Austria, mostly of the lower-middle class, and endangered their very existence. (29) At the time of the Anschluss there was little the Zionist Executive could do right away, since it had only 153 certificates at its disposal (of the 8,000 allotted for all the immigration categories for the period August 1937 to March 1938). For the next six months the Executive received one thousand labour certificates, of which it gave 170 to Austria, most originally designated for other countries including Germany. (30) The Zionist leadership was well aware that this was like a drop in the ocean, but they also knew there was no chance to get special certificates for Austria, beyond the fixed general quota. (31) The Anschluss aroused feelings of emergency similar to those experienced after Hitler's ascent to power five years earlier. However, in 1938 the situation was considerably worse than in 1933. Not only did the Jews of Austria experience in a few weeks what the Jews of Germany had gradually suffered over five years, but at that time the capability of Palestine to absorb newcomers was much lower, due to poor economic conditions and the curb on immigration imposed by Britain a few months earlier.

Since at that time immigration was not regulated on the basis of economic considerations, there was no point in trying to increase the labour schedule, and therefore the Zionists focused on the categories of immigration which were not subject, at least in the short term, to the ceiling imposed by the British Mandate authorities, mainly youth immigration (Youth Aliya) and the arrival of dependants. When dependants were again included in the total numbers, the Executive endeavored both to have them excluded from it and to extend the definition of eligibility for this category so that it would include not only minors under 18 of age and elderly parents over 55, but also, in the case of Austria, brothers and sisters. Additionally, the President of the Zionist Organisation, Chaim Weizmann, tried to convince the British government to issue 1,000 special immigration certificates for Austrian Jews; 400 for refugees based on the readiness of agricultural settlements to cover their maintenance and to employ them; 300 for members of pioneer organisations whose absorption would be financed by the Council for German Jews; 200 for experts invited by factories and manufacturers; and 100 for persecuted Zionists. (32)

Very little materialised from those efforts and they are depicted here not only for historical reasons but also to illustrate both the futility of the Zionist endeavors and the marginal role that Palestine could have played in solving the refugee problem, even had the British met the Zionist requests. After all, the numbers requested by the Zionists and turned down by the British were pitifully small.

The Evian Conference (6-15 July 1938)

A few days after the Anschluss, the American President, Franklin D. Roosevelt invited European and South American states to a conference on the issue of German refugees, assuring the participants that 'no country would be expected or asked to receive a greater number of immigrants than is permitted by its existing legislation'. The Zionist Executive was not aware of the silent Anglo-American understanding that Palestine would not be raised at the conference as a potential destination for the refugees, though they suspected this might be the case. (33) The discussion held at a meeting of the Zionist Executive prior to the Evian conference sheds light on the ideas and considerations that existed and evolved within the Zionist leadership. (34) The discussion reveals a clear awareness of the limited potential of Palestine as a destination for German Jews. Having admitted that Palestine was unable to solve the problem of the Third Reich's Jews, some members of the Executive were willing to have the Jewish Agency be involved in non-Zionist solutions, and proposed to ask the conference to work out an agreement with Germany on the orderly exit of the Jews with some of their property over a period of ten years. One third of these would emigrate to Palestine, one third to the U.S. and the rest to other countries. Most of the members, however, insisted on limiting Jewish Agency involvement to Palestine, leaving other agencies to deal with other destinations.

The discussion also exposes the concerns about the irrelevancy of Palestine as a solution to the crisis of German Jews, not only because of the political restrictions imposed by the British and the severe economic situation, but also because of the Arab Revolt, which had then reached its peak. The chairperson of the Zionist Executive, David Ben-Gurion, phrased it thus: --In the eyes of the world the situation in Palestine seems similar to that of Spain [afflicted by civil war]. A country experiencing riots, where bombs are thrown every day, people are killed and unemployment and economic stagnation prevail -- a country like that is no place for solving the refugee question.’ Knowing that Palestine could not provide a meaningful answer to the plight of the Jews of the Reich, members of the Executive worried lest the conference might totally eliminate Palestine from the list of immigration destinations, with the result that Jewish organisations would divert the contributions for aiding their refugee brethren to other countries.

The deliberations preceding the Evian conference mark the beginning of a change, which was to continue after Kristallnacht, towards perceiving the German crisis as being a massive refugee crisis rather than a matter of orderly immigration and, as such, calling for a whole new approach. This change of attitude was apparent in the plans contemplated to erect huge labour camps and employ newcomers in public works and private enterprises. However, most members of the Executive thought it was inconceivable to launch such a project when thousands in the country were unemployed.

The Zionist Executive also debated whether to send delegates to the Evian conference. Ben-Gurion recommended sending high-level officials, headed by the Organisation’s President, Weizmann, to make sure that the conference would not detach the problem of European Jews from Palestine. When it became clear that the Jewish case would be presented before a sub-committee and not in the plenary, that the Jewish Agency would not enjoy any official status, and that its representatives would appear before the sub-committee with a similar status to that of many other Jewish delegations, Zionist officials already in Evian advised Weizmann to stay at home. (35)

In the final analysis, the Zionists had no impact on either the proceedings of the conference or its outcome. The conference, attended by delegates of twenty-nine nations and representatives of thirty-nine private organisations, made no contribution to solving the problem of Jewish refugees from the Third Reich and did not ease their plight. Palestine was not considered as a possible destination, taking the British line that economic and political reasons meant it could not be opened to refugees, and therefore that it could not be considered as a country of settlement. (36) All in all the conference realised the pessimistic predictions of the Zionists, namely that the removal of Palestine from the list of destinations would not result in opening other countries' gates to Jewish immigration. (37)

The Kristallnacht Pogrom of 9-10 November 1938

In a coincidence that history produces every so often, two events which dramatically influenced the Zionist immigration policy took place within two days (9-10 November 1938): The Kristallnacht pogrom and the release of the Woodhead Commission report stating that the partition of Palestine and the establishment of a Jewish State in part of it, which had been proposed about a year and a half before by a British Royal Commission (better known as the Peel Commission), (38) were not practical. (39) Zionist reaction to Kristallnacht was therefore formulated under the shadow of the disturbing change -- from the Zionist point of view -- of Britain's Palestine policy. The combination in Kristallnacht of aggressive anti-Semitic policy initiated by the authorities, which had been the fate of Germany's Jews in various degrees of intensity since 1933, with the physical attack on their lives and property by violent crowds acting in accordance with instructions by the authority, in a mode typical of East European countries, led the Zionist leadership to realise that the Jews of the Reich were doomed and that they had to get out of Germany and Austria, and the sooner the better. Kristallnacht had a decisive impact on the transformation of the Zionist approach to the German crisis from conceiving it as being an immigration issue to constituting a refugee problem requiring emergency action. The Woodhead Report was also influential in forging a line of political action linking the refugee crisis with the establishment of a Jewish State in Palestine, and ruling out other ideas that would only divert attention from Palestine as a destination for the refugees without offering other feasible alternatives.

The idea of erecting temporary camps for young people from Germany financed by the Jewish people that had been raised prior to the Evian conference by junior members of the Zionist establishment was now expressed by the chairperson of the Zionist Executive himself: 'We will put up camps for hundreds of thousands. They will be better off here than in detention camps in Germany, and the Jewish people will take care of them after they get to Palestine'. (40) The feeling of emergency brought to the fore other, non-Zionist ideas. Werner (David) Senator, a representative of the non-Zionist wing of the Jewish Agency, put it bluntly: 'Since I do not see the likelihood of rescuing the Jewish people in Palestine alone, I cannot reject proposals aimed at rescuing some of the people in other countries'. (41) But the unequivocal stand of the two prominent Zionist leaders -- Ben-Gurion and Weizmann -- was to focus exclusively on solutions connected to Palestine.

There was an obvious discrepancy between the Zionists’ lofty public declarations and the modest actual plans they proposed. For instance, in late 1938, the Zionists demanded that 100,000 Jews from Germany be allowed to enter Palestine,(42) while in concrete negotiations the numbers added up to less than a quarter of this figure (22,500). (43) Moreover, a comparison of the solutions that Palestine was able to provide to the grandiose plans of the British Council for German Jewry may help to illustrate how modest the former were. In mid November 1938, when members of the Council asked the British Prime Minister that Britain take part in financing the emigration of 300,000 German Jews to various destinations, Weizmann asked him to open the gates of Palestine -- in spite of the severe economic situation there -- to 6,000 youngsters detained in concentration camps and 1,500 children, to be absorbed by monies of the British Council for German Jewry. (44) The National Council (ha-Va’ad ha’Le’umi) announced that the Yishuv would absorb 5,000 children from Germany in foster families and educational institutions, expecting, in this case as well, that world Jewry would shoulder the financing of the rescue operation. (45) A few days later the number was doubled; (46) however, both figures were more declarative than actual and the project never really materialised. (47)

At the same time Britain announced its intention to grant entrance to child refugees, whose maintenance would be financed either by their relatives or by other financial sources. (48) In reaction to this proposal Ben-Gurion made on 7 December 1938 a statement that turned out to be one of his most frequently cited quotations:

The demand to bring to Palestine children from Germany does not originate in our case only from feeling of pity for those children. Were I to know that all Germany’s [Jewish] children could be rescued by bringing them over to England, and only half by transporting them to Palestine, I would opt for the latter, because our concern is not only the personal interests of these children, but the historic interest of the Jewish people. (49) When this contentious saying was made, the Jewish Agency presented the demand to let the children enter Palestine as an ultimate condition for its participation in a conference Britain was about to convene to deal with the future of Palestine. The British pretext for refusing the arrival of the children to Palestine was that it would cause Arab boycott of the conference, and an infuriated Ben-Gurion said at the same meeting, that --even immigration of children is subject to the good grace of the Arabs’. (50)

Britain’s policy on Palestine in general and its immigration policy in particular were conceived by Ben-Gurion and other Zionist leaders as meant to placate the Arabs in Palestine and neighbouring countries and was depicted as component of the appeasement policy towards Nazi Germany prevailing at the time, especially after the Munich Agreement of September 1938. To put this controversial saying in context, it should also be noted that the word --rescue’ was not charged at the time with the fateful meanings of life and death it received during the Holocaust. (51) The fate of Ben-Gurion’s controversial stand in the matter of rescuing the children from Germany was similar to that of the Zionist position regarding the Evian conference: neither had an impact on the path of history, one way or the other. Nevertheless both have been subject to endless discussions and accusations and are often carelessly used as anti- Zionist ammunition. (52) For instance, a book criticizing the Zionist policy during the Holocaust counts the Zionist stand at the Evian conference as one of --the mistakes made by the Zionist movement during the Holocaust’, deploring Zionism for having --crucial influence in determining the course events took’ in that conference. (53) Ben-Gurion’s remark regarding the transfer of children was presented in another book as an example of Zionist betrayal of German Jewry, of Zionism turning its back on them. (54) Other scholars blame the accusers of Ben-Gurion and of Zionism of manipulative and insincere use of the quotation, though their own arguments in defending Ben-Gurion tend to be somewhat apologetic. But even those scholars, who do analyse the remark in its historical context, do not refrain from labeling it --unfortunate’, --brutal’, --stark’ or --bold’. (55) Attempts to Increase the Flow of German Jews to Palestine Encountering the German crisis generated some creative ideas and intensified some modes of operation that had already existed before, all intended to increase the flow of German Jews to Palestine beyond the limited quotas of the labour schedules. This was done either in cooperation with the relevant Governments -- the German and the British -- or illegally.

The Ha'avara Transfer Agreements (56)

In 1931, at the height of the world economic crisis, the German Government introduced the Reich Flight Tax, aimed to prevent the flight of capital abroad. (57) Whoever wished to leave the country or to transfer money to other countries, though relinquishing a considerable portion of his assets, could do so. At the turn of 1933-4, money could be taken out of Germany by handing over 23 per cent of its value; in 1936 the (loss of value reached 70 per cent and in 1939 until the outbreak of the war, it reached 95 per cent. (58) Wishing to get the utmost number of Jews out of Germany, the Nazi Government granted Palestine special status, allowing those emigrating there to take with them the minimum of £1,000 sterling required for the --Capitalist’ visa (category A) with almost no financial loss. (59) On 1 January 1935 the Germans limited the number of the people entitled to do so to only twenty per month, (60) and in April 1936 the special status was cancelled altogether. (61)

In 1933 Zionist institutions signed a series of agreements with the German Government intended to facilitate the accelerated transfer of Jewish property from Germany to Palestine (the Ha'avara Transfer Agreements). From the outset the Ha'avara was aimed at wealthy Jews who did not wish to leave a considerable portion of their property behind in Germany, as those who were willing to take only £1,000 sterling could have done so anyway in the first years of Nazi rule. (62) The initial Ha'avara Agreements set two channels of transferring money to Palestine. 'Account A' was destined for transferring money by immigrants. The potential immigrant deposited Reichsmarks in a special account in Germany used for the purchase of German goods to be exported to Palestine. After the goods were sold in Palestine, the Ha'avara company refunded the immigrant in Palestine, paying him in Palestine pounds, minus a commission. (63) 'Account B', opened at the request of the Jewish side, was intended to transfer money by Jews who wanted to invest in Palestine while remaining, at least for the time being, in Germany. Strange as it may sound, in the years from 1933 until late 1935 Palestine was an island of economic prosperity in a world struck by economic depression, and was considered an attractive destination for investment. 'Account B' was also intended for transferring contributions to Zionist funds. (64) The changes Germany made in the Ha'avara Agreements and the more severe rules it applied on exporting foreign currency, on one hand, and the limited ability of the Jewish market in Palestine to absorb German products on the other, caused a bottleneck in the Ha'avara pipeline. The amount of money deposited in the special accounts in Germany far exceeded the demand for German goods in Palestine, and the waiting line of potential immigrants grew longer and longer. In the second half of 1935 there were over 1,000 people on the waiting list, (65) and in November the number rose to 1,300.(66)In order to accelerate Jewish emigration by speeding up the use of the monies in 'Account A', the Germans blocked 'Account B' in April 1936, and the Ha'avara stopped being used as a vehicle for transferring monies other than that of immigrants. Nevertheless, at the end of August 1938 there was a total amount of about RM 83 million deposited in the Ha'avara account whereas in that entire year only RM19 million had been approved for transfer. (67)

In the first two years of its operation, the Ha'avara served mainly the following purposes: transferring money of wealthy immigrants who wished to bring substantial amounts of money to Palestine, well above the minimal £1,000 sterling; transferring investments of wealthy Jews who remained in Germany; and transferring contributions to Zionist funds and investments in private and public companies. After the Germans limited the number of Jews entitled to take out of the country the £1,000 sterling needed for the category A visa with no loss of money to only twenty a month (at the beginning of 1935), the Ha'avara became virtually the only avenue of immigration for wealthy German Jews to Palestine. This amendment of policy generated a change in the composition of Ha'avara users, increasing the absolute and relative numbers of those using it to transfer the minimal amount of money needed for immigration as a person of independent means.

In the early phases of the Ha'avara Agreement a decisive factor in motivating the German authorities to give preference to emigration to Palestine was the fear of a reduced level of German exports due to a world-wide boycott of German goods. They found the Ha'avara particularly attractive since it served their goal of pushing Jews out of Germany while it could also be utilised to promote another goal, that of increasing German exports to Palestine and the Middle East. A circular issued by the Ministry of Economics in August 1933 stated clearly that the agreement was concluded 'in order to promote the emigration of German Jews to Palestine through the allocation of the necessary amounts without excessive strain on the currency holdings of the Reichsbank, and at the same time to increase German exports to Palestine'. (69) Four years later the Nazis still found the Ha'avara to be 'the cheapest way -- in respect to foreign exchange -- to facilitate Jewish emigration'. (69) However, in later phases, the crucial factor in giving continued preference to emigration to Palestine was the diminishing availability of destinations allowing the immigration of German Jews. The Nazis wanted the Jews out of the country, and Palestine, even given the restrictions of the Mandate government, appeared to be almost the only country open for organised large-scale absorption of Jewish immigrants, with the Zionist Organisation being the only Jewish organ capable of implementing and spurring emigration on such scale to Palestine. However, by the end of 1938, after Kristallnacht, it was clear to the Nazis that the Jews were sufficiently motivated to emigrate that they would do so even if they had to leave their possessions behind, and thus there was no longer need to promote Jewish emigration to Palestine (and elsewhere) by easing and facilitating the transfer of assets. (70)

All in all the Ha'avara served as vehicle for transferring £P8,100,000 (Palestine sterling) from Germany to Palestine. (71) This was equivalent to RM140 million, which constituted only about 1-1.5 per cent of Jewish property in Germany. (72) Only 30 per cent of the Ha'avara monies (about £2.5 million Palestine sterling) were used to cover the £1,000 needed for category A visas, (73) bringing the number of immigrants who got their visas through this arrangement, and could not have acquired them in any other way, to about 2,500. An immigrant coming to Palestine with category A visa brought along with him, on average, slightly over one dependant, (74) thus the Ha'avara directly facilitated the immigration to Palestine of about 5,000 Jews from the Third Reich, mostly from Germany. The advantages of the Ha'avara were, however, even more profound. The money brought in by category A immigrants, in particular by those who brought in sums well above the minimum; and the money invested in public and private companies and enterprises, as well as contributions to the Zionist funds, all contributed to the development of the Jewish economy in Palestine, increased its absorptive capacity and thus, directly and indirectly, facilitated the immigration to Palestine of thousands of more Jews from Germany and other countries.

Though fully aware of the economic potential of the Ha'avara, the Zionist Organisation was at first hesitant about conducting direct and open negotiations with the Nazi authorities, out of concern about the negative reaction of Zionist, Jewish and world public opinion at a time when Jewish and other organisations were advocating the boycott of German products. (75) Therefore, in the first two years, negotiations on the Jewish side were mainly conducted by representatives of private enterprises, by semi-official Zionist delegates and by the Anglo-Palestine Bank. Only in 1935, after the situation of Germany's Jews had deteriorated and more severe obstacles were placed on exporting foreign currency, did the Zionist Organisation openly deal with the Ha'avara and officially adopt it and put it under the supervision of the Zionist Executive. (76) In this way, the Ha'avara also strengthened the Zionist Organisation's control over the flow of money to Palestine and rendered it more influential as to how it was invested. (77)

Youth Immigration (Youth Aliya)

Youth Aliya, the organized immigration to Palestine of Jewish teenagers, first from Nazi Germany and then from other countries, was founded in 1933 and its first group arrived in Palestine in February 1934. (78) Financed by the Zionist Organisation and other Jewish funds, Youth Aliya entailed preparing teenagers in Germany to live in Palestine by teaching them Hebrew, Jewish studies and Zionist history, literature and songs, and training them for agricultural work; secured their visas and transportation to Palestine; and ensured their education in Jewish agricultural settlements, mostly kibbutzim (communal settlements) and in boarding schools. Some 5,000 Youth Aliya teenagers came to Palestine before the Second World War.

Most Youth Aliya youngsters came from Germany for three main reasons. The emergency situation in Germany prompted parents to send their children on their own to a distant Asiatic country. Next, a large proportion of the funds financing the project were earmarked only for the absorption of German youth. And finally, Britain made it implicitly clear to the Zionist Organisation that Youth Aliya should be limited to candidates from Germany (and from March 1938 to Austria as well), otherwise this type of immigration would also be put under the quota system. (79) Youth Aliya's immigrants, aged from 14 to 17, came under Category B, which was not subject to quotas or numerical restrictions, thus leading to a net increase in the number of immigrants to Palestine. However when the first youngsters graduated from educational programs and were about to join the labour market in 1936, the government included their number in the calculation of the economic absorptive capacity of the country, so eventually, the Youth Aliya immigrants from Germany did affect the number of permits issued under the labour schedules. (80)

Another project, similar in some respects to Youth Aliya but on a much smaller scale, was 'Training in Palestine', initiated in 1936 by Sir Herbert Samuel, the first British High Commissioner for Palestine. The idea was that since it had become more and more difficult to run training programs in Germany, young people would be brought to Palestine, beyond the labour quota, for the purpose of training them there for agricultural work. The Council for German Jewry financed the maintenance and training of the newcomers in their first year in Palestine, but once they joined the labour market, the number of participants, 200, was deducted from the labour schedule. (81)

After the Anschluss, the Zionist Organisation asked that in the case of Austria the age ceiling for eligibility to Youth Aliya be raised in order to bring to Palestine 800 youngsters over the age of 18 outside of the labour quota to be trained for agricultural work. (82) Like many other efforts and experiments, this one too was futile, exemplifying once again how ineffectual and frustrating the activity of the Zionist Organisation was in the face of the accelerating German crisis, and how modest even their unfulfilled plans were.

Illegal Immigration

From 1932 on, the demand for immigration to Palestine exceeded the supply of labour certificates. This situation not only generated competition over the certificates but also increased the volume of illegal immigrants into Palestine. Illegal immigration existed from the very beginning of the Mandate period, carried out through three main methods: smuggling immigrants across land and sea borders, entering Palestine as tourists and remaining in the country after the tourist visa had expired, and fictitious marriage. At the beginning of the 1930s, organized illegal immigration of 'tourists' was added, and in 1934 the first ships carrying illegal immigrants approached the shores of Palestine, a method fully-developed several years later. All in all, more than 20,000 immigrants attempted to make their way to Palestine on illegal ships in the years 1937-9. Some of these were intercepted, but others did manage to put their passengers ashore. (83) Until 1937, German Jews seldom used these methods, as the legal routes were more available for them than for Jews from other countries. However, in 1937, when the total number of immigrants was drastically reduced and the number of immigrants of independent means (category A) allowed to enter Palestine also lessened, a new method was soon to develop: wealthy Jews from Germany entered Palestine with a tourist visa and after a while applied for permanent residency as category A immigrants. This practice became widespread after Kristallnacht, when the demand for type A certificates much exceeded the supply. As a rule, tourists wishing to register as permanent residents had to leave Palestine, return to their country of origin and apply there for the visa. Until the spring of 1939 tourists from the Third Reich and Italy, considered 'countries of persecution', were exempt from this demand. (84) In June 1939 the government applied the rule to all, with no exceptions, notifying the Jewish Agency that people already in Palestine would be legalized but no new applications would be handled. (85) On the eve of the war, the government announced that its Immigration Department would not register any more tourists as immigrants. (86) The new regulations meant that Jews from the Third Reich who entered Palestine without an immigrant visa could not get one at all, as returning to their countries of origin was out of the question, certainly after war broke out.

In the last year before the war (after Kristallnacht), illegal immigrants from Germany and Austria (and after March 1939 from Czechoslovakia as well) were, for all practical purposes, refugees, as was the case with many of the legal immigrants arriving from those countries. The adjective 'legal' or 'illegal' refers to whether they possessed a legal visa to enter Palestine, but all were fleeing their country of origin not of their own free will and were stripped of almost all their property and financial means. Well-to-do people, who had no way of getting their money out of Germany and no legal permit to enter Palestine used the last of their resources to get on rickety boats and begin a dangerous voyage across the Mediterranean Sea to enter Palestine clandestinely.

In 1937-8 the British authorities were not yet prepared to block the ships loaded with illegal immigrants and they did not intercept even one. In 1939 many ships were captured and their passengers either detained in Palestine or deported. Another measure employed by the government was the deduction of the number of illegal immigrants, either accurate or assumed, from the immigration quotas. In the Spring of 1939, the government deducted the number of illegal immigrants not only from the yearly quota of 10,000 immigrants fixed by the MacDonald white paper but also from the refugee quota (of 25,000 for the next five years), claiming that some of the illegal immigrants came from countries for which that quota was originally intended. The government informed the Zionist Executive that its records showed that the number of illegal immigrants was even higher but for lack of hard evidence it only deducted 1,300 certificates. It warned the Executive that should illegal immigration continue at the same pace, the government would consider giving no certificates at all either to immigrants or to refugees for the season beginning October 31. (87) In July 1939 it carried out the warning, (88) and in fifteen of the first thirty-nine months of the war the Mandate Government did not issue any schedules for legal immigration, (89) while emigration of Jews from the Reich and from certain occupied areas was not only possible, but also favoured, encouraged and promoted by the Germans. Only in late October 1941 was emigration of Jews from the Reich banned by the Nazi regime. (90) Due to the immigration policy pursued by the British in Palestine, including prohibiting people from Germany or from German-occupied territory from entering Palestine (mentioned above) in those crucial months, the only possible way for Jews from the Reich to enter Palestine was through illegal immigration.

From 1938 until early 1941 Nazi officials and Jewish individuals representing various elements of Zionism (and sometimes themselves) had contacts whose aim was to further Jewish emigration from the Reich and immigration into Palestine. (91) The most prominent person involved in those contacts from the German side was Adolf Eichmann, who arrived in Vienna in March 1938 as the Gestapo delegate in charge of emigrating Jews, and established there the Central Office for Jewish Emigration in August. From then onwards, both before and after Kristallnacht, various organisers of illegal immigration to Palestine -- either affiliated with the Zionist organisation, belonging to the dissenting Revisionist Party or private organisers -- turned to Eichmann's office in Vienna for assistance in getting Jews out through neighbouring states to a port where they could board boats taking them clandestinely to Palestine. It was only the Gestapo that could, and was willing to help, with all the technical, financial and bureaucratic red tape involved in such complex operations. In addition to providing Jews exit permits against the surrender of all their property, Eichmann's Central Office in Vienna assisted in releasing from concentration camps individuals who were promised to have places on illegal immigration transports heading to Palestine. At the beginning of 1939 a Central Office was established in Berlin and Eichmann soon became responsible for Jewish immigration from the whole Reich. In this capacity he had contacts with the various organisers of illegal immigration mentioned above, but they did not lead to any actual transports taking place.

In early 1939 Eichmann, probably in order to weaken the Zionists, nominated his own Jewish agent to coordinate illegal immigration matters, and a year later he nominated him to be the sole agent in charge of Jewish immigration, both legal and illegal. The coordinator, Berthold Storfer, had become active in Jewish affairs only after the Anschluss, and in his role as member of the Austrian Jewish leadership he had contacts with Eichmann with the aim of facilitating more Jewish emigration. Zionist emissaries in the Reich were reluctant to cooperate with Storfer, whom they considered a traitor collaborating with the devil. Storfer's ventures were funded to a great extent by the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (AJDC), a non-Zionist organisation. His plans to send illegal ships to Palestine did not materialise before the war, and it was exactly a year after the war broke out that about 3,600 refugees left Vienna and Bratislava (Slovakia) on their way to Palestine on a transport he had organised. They arrived in Palestine on three boats in late November 1940, but were not allowed into the country. The British announced they would be deported to Mauritius, an island in the Indian Ocean and never will be permitted to enter Palestine. The passengers of two boats were already transferred to a deportation ship, Patria, when the Haganah, the military arm of the Yishuv, blew it up in what had been planned to be a limited scale sabotage intended only to disable the ship from sailing to Mauritius. Close to three hundred people died, and those who survived the sunken ship were allowed to remain in Palestine. The approximately 1,600 passengers of the third boat were deported to Mauritius and brought back to Palestine only after the war was over. (92)

The purpose of organised illegal immigration in 1938-9 was not limited to the rescue of Jews fleeing from Nazi ruled areas but also to serve as a component of Zionist policy. The arrival of the ships and the protest activity of the Yishuv over the detention and deportation of the immigrants aimed at mass communication, public opinion and policy makers, with the ultimate purpose of creating a linkage between the solution to the problem of Jewish refugees in Europe and the establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine. Neither aim -- the humanitarian nor the political -- was achieved by the time the Second World War broke out.

Conclusions

Three cardinal factors were involved in turning Palestine into one of the major destinations for immigrants and refugees from Nazi Germany -- British policy, Jewish philanthropy, and Zionist activity, each having an inconsistent impact on the final outcome. The basic, and negative, feature of Britain's role was its restrictive immigration policy, particularly from 1937 on. Next in importance, and a positive feature, was the preference that Britain gave to German Jews in immigration to Palestine over their brethren from other countries. However, negatively again, Britain never devised special allotments for German Jews beyond the regular quotas, and from the end of 1935, when the situation of the Jews in Germany steadily worsened, Britain consistently cut down on the overall number of Jewish immigrants allowed to enter Palestine and reduced the special benefits granted to German Jews.

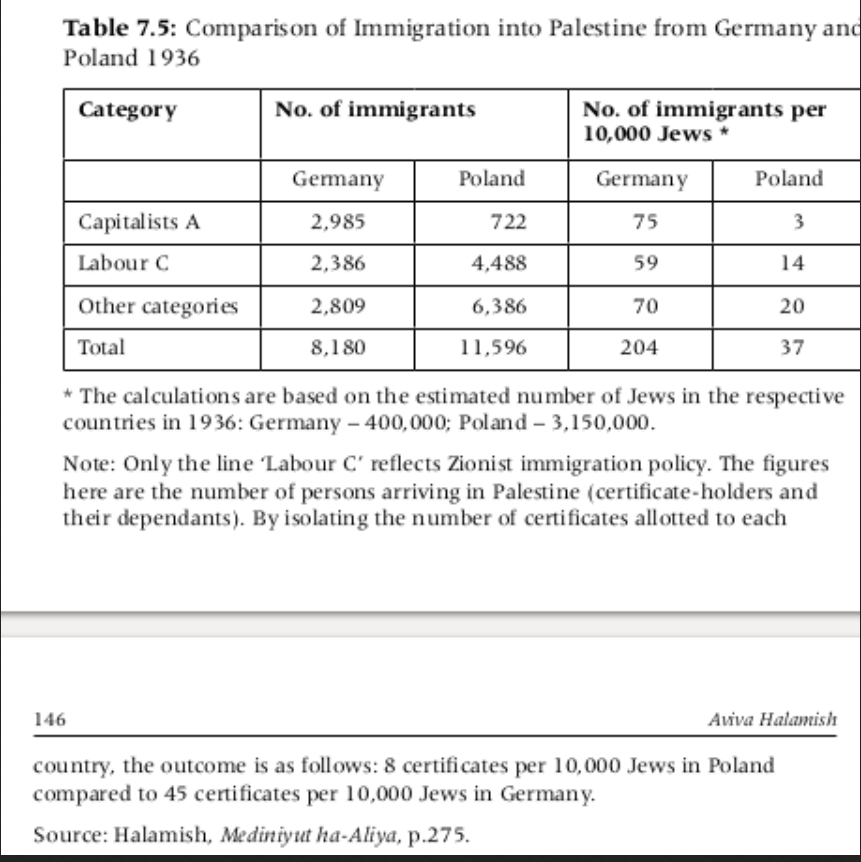

Jewish organisations and individuals launched philanthropic campaigns to assist the immigration and resettlement of German Jews more than for other Jewish communities before and during the German crisis. They did so, to a large extent, because they felt more akin to German Jews than to other distressed Jewish communities in terms of their lifestyle and status in the general community. To put it in familial phrasing, our rich cousin, the post-Emancipation, educated and affluent German Jew who suddenly became ill, deserved better treatment than our poor and chronically ill cousin (the Polish Jew). (93) Contributions for the relocation of German immigrants in Palestine were destined for them only, and, combined with the affirmative policy of the Mandate Government, their chances both to get certificates and to be properly resettled were much greater than of Jews from other countries. In 1936, a German Jew's chances of receiving a certificate were four times greater than those of a Polish Jew (see Table 7.5).

The good will of the Zionist Organisation towards immigrants was fundamental, not only as an act of national solidarity but also as a means to increase the Jewish population of Palestine as a step in achieving sovereignty. However, more than anything else, Zionist activity regarding the German crisis was a reaction to and the result of the first two factors -- British dictates and Jewish philanthropic preferences. The Zionist Organisation's receptive attitude towards immigrants from Germany was curtailed by considerations stemming from its accountability to its members in other countries and concern for other Jewish communities in distress as well as by the raison d'être of its very existence as an organisation. The Zionist Executive was walking a narrow path. On the one hand it needed to continue helping German Jews because, among other factors, the flow of money into Palestine was dependent on the continuation of immigration from Germany. On the other hand, it had to be loyal to its members in countries with larger Zionist constituencies. Decision making was even more difficult because conflicting data and predictions ruled out a rational evaluation of the relative danger facing the various European Jewish communities.

Until 1938 the tension between the Zionists and other Jewish organisations focused on matters of fund raising and distribution. At the Evian conference there was a dispute over the question of who should present the Jewish cause and who should represent the Jews. Later on, after Kristallnacht, the Zionists were worried that ideas for solving the German refugee crisis, other than Palestine, would only divert attention from Palestine without suggesting feasible alternatives. Though the Jewish front was divided, it is difficult to point to the negative impact this had on the flow of German Jews to Palestine in particular, or on the handling of the crisis in general.

Finally, let the figures again speak for themselves. The Jewish population of Palestine at the beginning of the German crisis was approximately 200,000 and reached about 450,000 at the outbreak of the Second World War. In about seven years, the Yishuv absorbed almost 60,000 Jews from the Third Reich. Without going into the detailed annual ratio of immigrants from Germany, it is sufficient to conclude that Palestine, which was second only to the United States in the absolute number of immigrants from Germany, was by far the first in terms of German Jewish immigrants and refugees in proportion to its existing population.

Tables

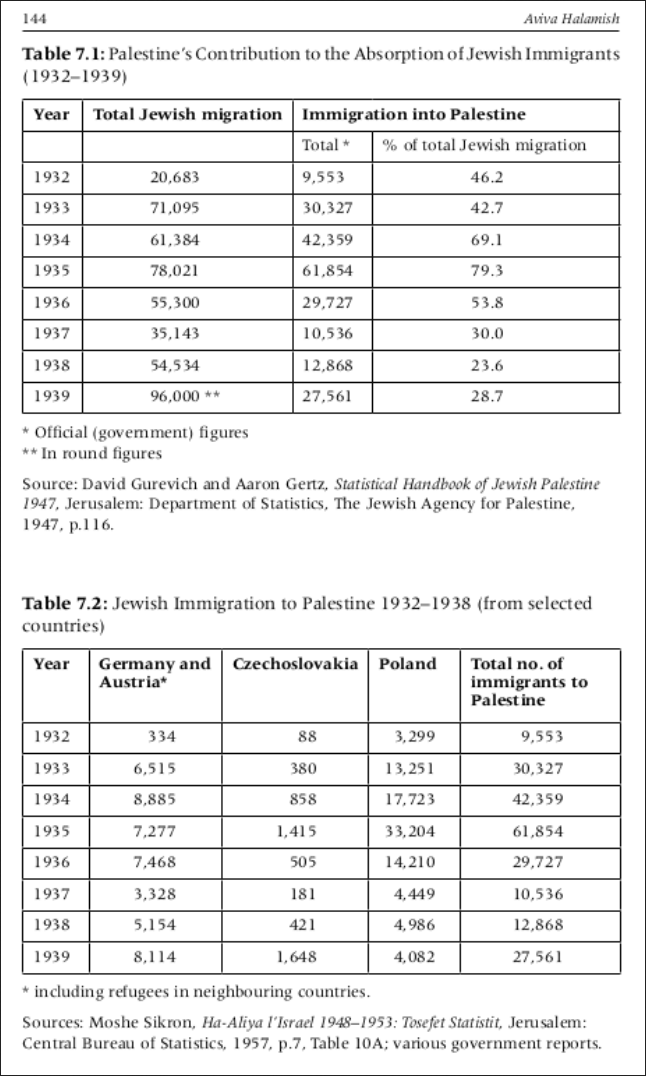

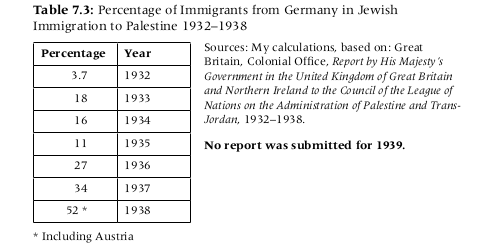

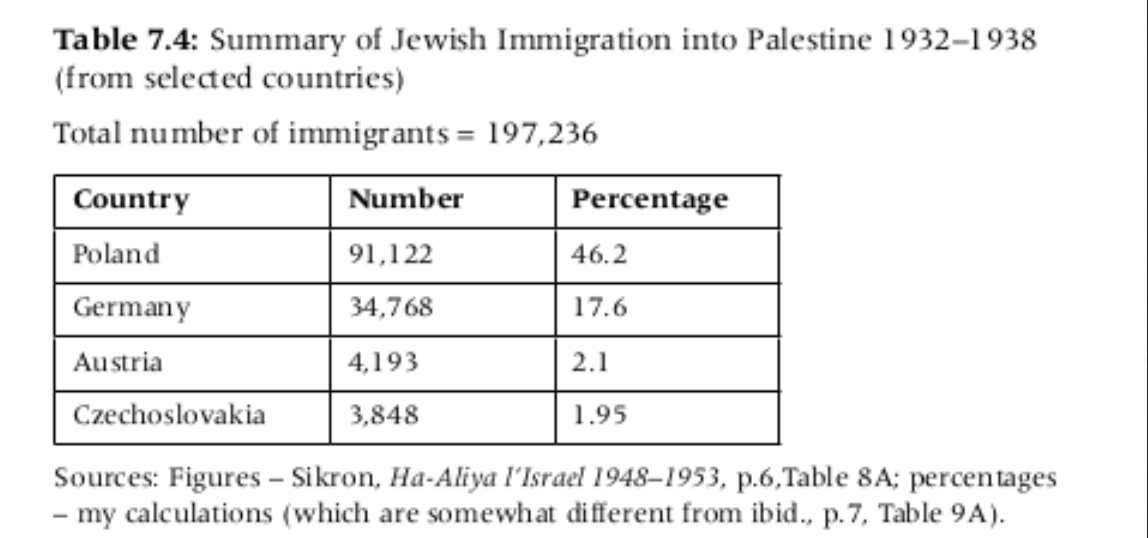

General note to the tables: The figures in the following tables are based on official Government data, which does not include unregistered illegal immigrants.

Notes

Click here if you wish to read this article in PDF format.

Post Your Comment

*It should be NOTED that your email address won't be shared, and all communications between members will be routed via the website's mail server.